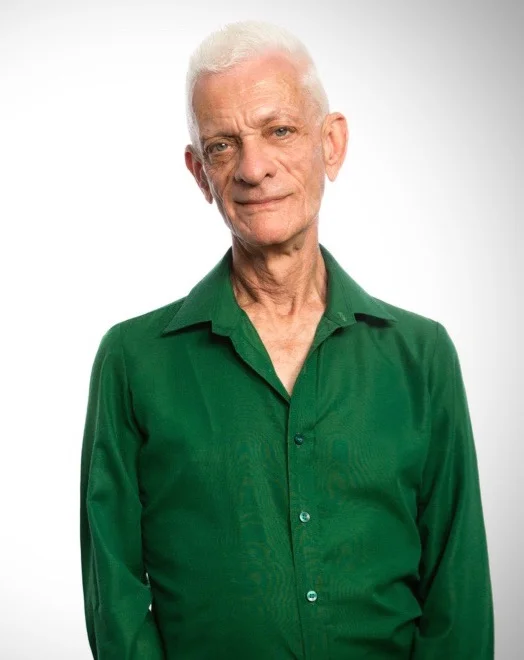

ROBERT DESSAIX

Interview by Madeleine Dore

This article was originally published on Kill Your Darlings

Robert Dessaix:

Writer

Robert Dessaix never intended to be a writer. ‘It hadn’t crossed my mind really. But I wrote my first book, A Mother’s Disgrace because when I told another Australian writer the story of how I met my birth mother, she said to me, “Well, if you don’t write that book, I will write it,” so I went away and wrote it!’

The seemingly spontaneous decision mirrors other pivots in the 73-year-old’s career, like the time he went from working as an academic to the presenter of Books and Writing for Radio National.

‘After twenty years working as an academic, I had heard every single thing that any human being can possibly say about 19th century Russian literature – I may as well have been be putting tomato sauce into bottles in a factory.’

Bored one afternoon and walking past the ABC offices, he caught the lift up to the fifth floor and said to a programmer at Radio National that if he had a job, to get in touch. ‘About a month later he did!’

Such flexibility to shift throughout his career, he explains, may be in large part afforded by not having children. ‘It means you don’t have certain things, of course, but it does mean you have freedom. No one else is going to starve if you starve. You are not responsible to anybody so you can take risks, but the downside is not having family. I don’t have any family you see, I have a partner, but I don’t have any family.’

Most of Dessaix’s days are spent working on different writing projects, taking an all important nap after lunch, and touring the festival circuit promoting his latest book, The Pleasures of Leisure (Knopf Australia).

‘Sounds extraordinary, all that time spent promoting something that is already done.’

Dessaix starts each book with a fresh A4 Spirax five-subject notebook and divides the sections into themes, ideas for structure, books to read, movies to watch, random thoughts, and slips newspaper cuttings into the pockets.

‘Before I write a book – this is very important – I read through the notebook before doing the creative work and then I read the book again after it’s done and write down the things I forgot to include. Then I go through the manuscript to see if I can fit them in.’

Dessaix also keeps a pocket-size day book with him at all times to jot things down, and later transcribes it into the larger notebook. ‘I go through all my day books every few years and see if something comes out. It’s like putting stuff through a sieve.’

Like a sieve, the creative process can sometimes flow smoothly; sometimes those lumps just won’t budge. In The Pleasures of Leisure, Dessaix warns against turning your passion into your work or livelihood, but in our conversation, makes an exception for creative workers.

‘Creative workers are in a very special position, in that they work their passion. And that is why we can get particularly hurt, because we have invested so much of ourselves into our work.

‘So I can’t really say to someone to not write as work if you are passionate about it, but I can say you should only do it if you love it. If you feel restored and magnified by what you do, then do it. That will counteract the hurt.’

““I go through all my day books every few years and see if something comes out. It’s like putting stuff through a sieve.””

A day in the life

Morning

There’s this ideal picture of a writer getting up and going to the desk and writing something brilliant. This is nonsense. Life is not like that.

When I have a project underway – and there isn’t always a project underway, but when there is – what I try to do is have four days a week basically for the project, and aim to work in the mornings.

““There’s this ideal picture of a writer getting up and going to the desk and writing something brilliant. This is nonsense. Life is not like that.””

I’ll work on the project from about 9.30am or 10 till lunch. And lunch is a moveable feast – you can have it at 12.30pm if nothing much is happening, or you can have it at 1.45pm if something is.

I don’t try to work all day, I don’t think you should – I think you get tired of your own voice. Three hours is enough, I think, to talk to yourself in writing, four hours at most – after that you start to bore yourself.

Of course, writing also involves reading in order to inform yourself, so I would still regard it as a writing morning even if I am reading an essay for the book, or I’m looking at photographs or I’m meeting someone for the book I’m writing. It’s all work.

Afternoon

After lunch, I have my siesta. It has been scientifically proven that a siesta imprints on your mind what you have just learnt that morning, so you must have a siesta, it’s absolutely vital.

When I get up again at two o’clock, I’ll have a cup of tea, meet a friend or read a book or look at a magazine. I’ll do something lovely and then it’s time to say take the dog to the vet, or go to the supermarket.

People with children just say you’re crazy, you can’t have a day like that. But if you have children, that is your problem, I’m not going to live as if I do!

Evening

My evenings are not interesting – I rarely go out in the evening, just six times a year, to a concert.

My partner and I either watch television from the same chairs we take our siesta in, together with the dog, or a movie. We entertain once a year.

Then at about ten o’clock I toddle off to bed, and often listen to ABC FM. Early to bed and late to rise is my motto.

Middle of the night

I don’t feel envious of other people’s success because I have had a beautiful life. It would be ungracious of me to feel those things, but I suppose like any human being, I wake up at three o’clock in the morning sometimes and I think, why is he or she getting all this attention?

Why do I open up the Monthly or the Saturday Paper or the New York Review of Books and find XYZ is interviewed, when XYZ can’t write to save his or her life? Why is he or she world famous, and no one is paying attention to me? Of course I do, of course I wake up and think those things, who doesn’t?

But as one writer said to me; even for world famous writers, it is not enough. It is never enough. It doesn’t matter how much attention you are getting, it’s never enough. We all want more attention at three o’clock in the morning.

Weekend

On Saturdays, human beings in our society go to Bunnings – so you fix something that needs to be fixed, and you do jobs.

Sundays are for Sabbath. Doesn’t matter if you’re a believer or not, Sunday is when you do lovely things, you do restful things and restorative things – it could be gardening, or it could be a picnic, or it could be reading a book.

Behind the scenes

On buttonholing as a writing style…

““In my mind when I am writing, I am buttonholing a woman called Susie…someone who is very fond of me, but not completely uncritical.””

I buttonhole people when I write. In my mind, the reader is a mature, older woman who has lived a little bit, a woman who has suffered a bit, an educated woman – they are always the best to buttonhole because you can hear her talking back to you, and they tell you what they think and what they feel.

It’s not exactly gossip – I have used the word gossip – but gossip is usually trivial, but buttonholing can be very serious. So in my mind when I am writing, I am buttonholing a woman called Susie – Susie is someone who is very fond of me, but not completely uncritical – and I am telling her about all the things that make me happy and alive and interested and pleased to be here.

That is the way I write; not everyone writes that way. But by buttonholing Susie I don’t have to think about what lots of people are going to think is funny or boring. I just tell Susie, and everyone else eavesdrops.

On finding an audience for your work…

I’m only moderately well known – I’m not on the A-list. I’m not Tim Winton, Helen Garner, Richard Flanagan… I’m in some sort of B-list, but still, I have an audience. I have five to ten thousand Australians who will go out and buy whatever I write.

You have got to have more than 3,000 people or else no one is going to publish you. Either they have to think they will find over 3,000 or more or you have to show that you can attract more.

The difficulty is going to come with your second book, not your first. You may be able to convince somebody with the first, but it is hard to get your second book if you only sell 200, 300 copies of your first. So you should really only do this – since so few people are going to end up being successful – if you love doing it.

On writing about the chasm that opens at your feet…

Now that I can get published, I still don’t want to spend two or three years of my life on a subject that is not absorbing me.

I write a book, usually, that has opened at my feet. I write in order to leap across this chasm – the first book was when I met my birth mother and I was a disappointment to her, so I wrote a book explaining to her that it was all right to be me.

With each book, I try to resolve something that is a challenge. If I don’t feel there is a chasm, I don’t feel a great need to take a leap on the wings of a book. I can keep going to Centrelink and that will prevent me from starving to death.

But what I learned with my first book is that while I’m writing to resolve a challenge, no one cares about me. I am not important, and indeed when people wrote me letters about my first book, they would say thank you for your book about being adopted and meeting your biological mother, and then they would tell me all about themselves. What I had done is given them permission to talk and think and write about themselves. In writing my own story, I had magnified them. So if you are writing in order to tell us about your fascinating life, forget it. No one gives a stuff. No one cares about you and your mother; they care about themselves and their mothers.