You don’t have to figure out what you want in life

Words by Madeleine Dore

&

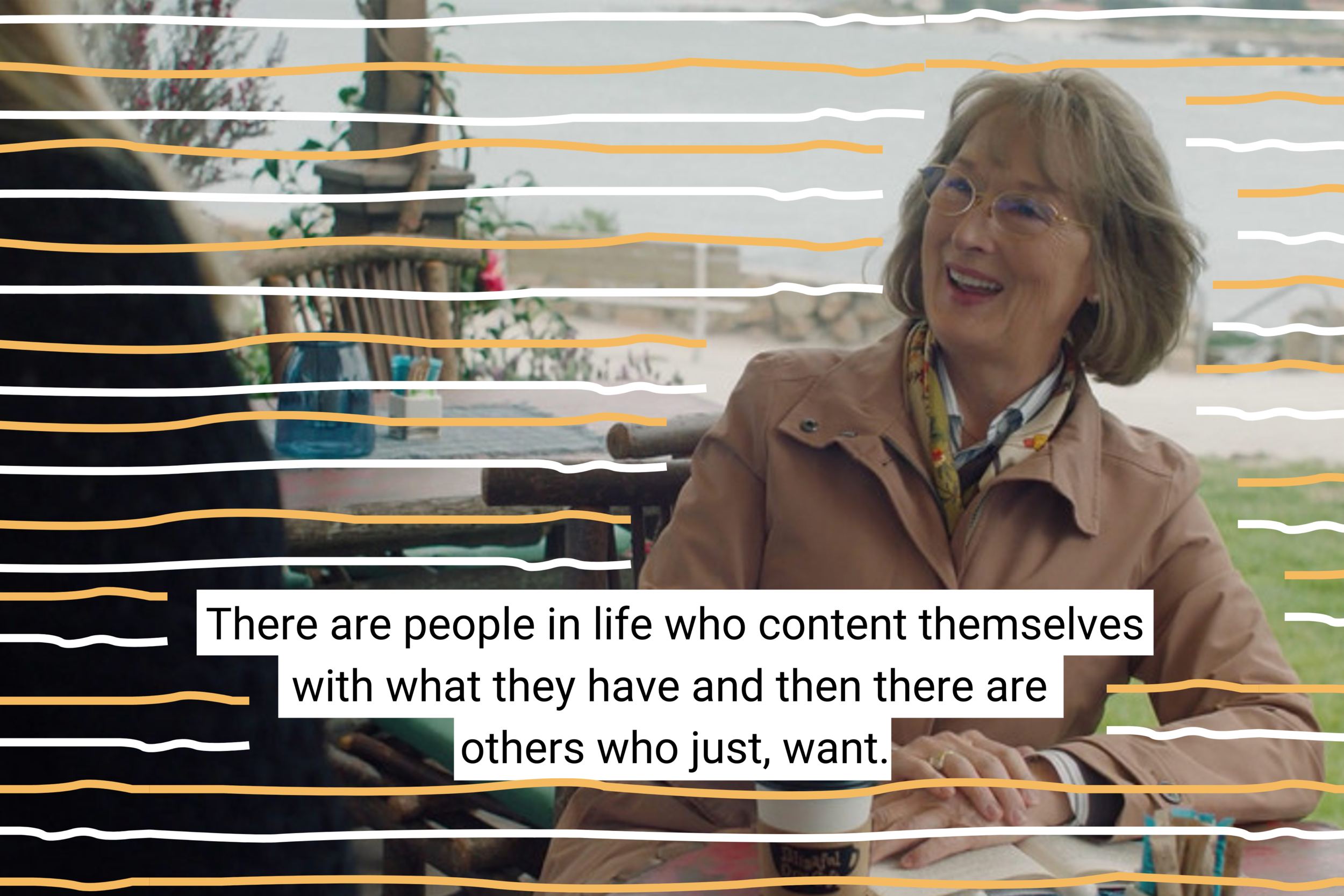

Image: Meryl Streep talking to Reese Witherspoon on Big Little Lies via HBO

A personal symptom of being creatively or professionally stuck is asking myself ‘how’ repeatedly.

How will I build my career?

How will I find love?

How will I figure out what I want to do with my life?

These questions are seductive to the part of us that craves certainty, assurance or is feeling idle on a Tuesday afternoon, but in many ways they are redundant – big life events such as finding love and career-defining often can’t be planned for or delivered neatly packaged.

Asking how can keep us stuck and powerless because the future is uncertain and we will never quite know exactly how it unfolds.

As dancer and choreographer Agnes de Mille once said:

“Living is a form of not being sure, not knowing what next or how. The moment you know how, you begin to die a little. The artist never entirely knows. We guess. We may be wrong, but we take leap after leap in the dark.”

To get unstuck, we must stop asking how and instead focus on the next step or action – even if it’s just a faint outline, a leap in the dark.

What can assist with this process of embracing uncertainty can be to figure out what you want. As Julia Cameron writes in The Artist’s Way, “When you figure out what you want, the how takes care of itself.”

On the page, it’s sound starting point. But as I admitted in my reflections on finishing The Artist’s Way, knowing what you want can be a hurdle in itself.

I’ve long struggled to figure out what I want – and even the times where I have appeared to get what I wanted, it’s so fleeting and temporary that I am still left wanting, or focused on the next want.

Wanting seems insatiable – and with this perpetual wanting we can wind up somewhere far from who we really are or ought to be.

The tensions and complexities of wanting

Figuring out what we want can create a tension within ourselves – we might struggle with giving ourselves permission to want, or find it difficult to ask for what we want, or have negative associations with being a wanter.

In the second season of Big Little Lies, a conversation between Meryl Streep and Reese Witherspoon’s characters – Mary Louise and Madeline respectively – puts the sense of shame that comes with wanting front and centre.

After tense small talk Mary Louise says to Madeline:

“You know, you seem like a nice person, loving, but you also strike me as a wanter. There are people in life who content themselves with what they have and then there are other who just, want.”

“I’m not a wanter,” responds Madeline.

“Oh you don’t take it personally. Anyway, I’m a wanter myself,” adds Mary Louise.

We don’t want to be wanters. We don’t want to perpetually want something more than what we have, even though so much of what we internalise from society about our careers or success is to strive, to leap, to go after the next thing, to want bigger things for ourselves.

In another episode of Big Little Lies, Renata played by Laura Dern picks up her husband Gordan from court after he has been arrested for several white collar crimes, bankrupting them both.

“Give me one fucking reason?” asks Renata.

“I wanted a Gulfstream,” says Gordon.

“Fucking pitiful,” says Renata.

“We are creatures of want. Jesus. You know, we are. Me and you… God, especially you.”

Renata’s response is to kick him out of the car then and there.

When we are described as wanters or creatures of want, we are defensive and ashamed.

Yet there is a societal expectation to figure out what we want – from a young age, we are asked what we want to be when we grow up, what we want to study, what we want in a partner, what we want our dream home to be, what we want to own and possess, what we want our lives to be life.

What tension, what conflict, what confusion – how do we want, but not be a wanter?

Perhaps it’s what we want that causes the tension. Material items, certain career opportunities, certain romantic partners, and certain salaries could be described as shallow wants. If our wants are shallow, of course we don’t want them to encapsulate our character.

As the philosopher Alan Watts puts it, perhaps we are all too aware that our wants or desires are “all retch and no vomit.”

When we place shallow wants such as money or material items as the most important thing, “you will spend your life completely wasting your time,” says Watts.

“You will be doing things you don’t like doing in order to go on living that is to go on doing things you don’t like doing. Which is stupid. Better to have a short life full of what you like doing, than a long life spent in a miserable way.”

Finding the deeper want

We’ve all experienced this thrashing between mismatched lives of what we thought we wanted because it was safe, logical or expected of us and what we really want to be doing.

One possible way to discern which of our wants are internalised by society and which are coming from something deep within us is to listen to our creative and exploratory self.

This particular self is often fine to admit it doesn’t know, or even actively resists the notion of wanting, and instead craves an escape from the want.

In The Onion, a 1995 work created by Marina Abramović, the performance artist devours a raw onion while repeating the following:

I am tired from changing planes so often, waiting in the waiting rooms, bus stations,

train stations, airports.

I am tired of waiting for endless passport controls.

Fast shopping in the shopping malls.

I’m tired of more and more career decisions, museum and gallery openings, endless

receptions, standing around with a glass of plain water, pretending that I’m

interested in conversations.

I’m so tired of my migraine attacks, lonely hotel rooms, dirty bed sheets, room

services, long distance telephone calls, bad TV Movies.

I’m tired of always falling in love with the wrong man; tired of being ashamed of my

nose being too big, of my ass being too large; ashamed about the war in Yugoslavia.

I want to go away, somewhere so far, that I’m unreachable by telephone or fax.

I want to get old, really old, so that nothing matters anymore.

I want to understand and see clearly what is behind all of this.

I want not to want anymore.

We want to be relinquished of our superficial wants and instead connect to a deeper want – a want to not want anymore.

In season six of Younger, the stylish head of marketing at the publishing company Diana Trout writes a Modern Romance column that’s published in a New York paper after a couples quarrel with her partner, Enzo.

In the article, she describes her own epiphany about finding the deeper want:

“Dreams we have as a child, dreams packed in a box for college, dreams you unpack when you move into you first apartment. Who you’ll meet, where you’ll work, who you will fall in love with. Think you have it all figured out? Life has better ideas, a bigger imagination, takes bigger chances than someone like me, a year ago, moving through her 40s in a cloud of old ideas. Life gives you more than you thought, but maybe not in the package you expected. It’s deeper than that, it is what you need underneath the want. It gives you what you can’t breathe without.”

Often what we can’t breathe without is the deeper want – but we often can’t find that through plans, lists or searching.

As psychologist and meditation teacher Tara Brach put it, it’s not about grasping for the particular, but connecting to the deep longing.

“Your wants are too small, make them larger, make them deeper. Make them all-encompassing.”

So what is an all-encompassing want? To quote Alan Watts, when try to figure out what we want in a naïve way, we often try to control everything, but we soon realise that’s not what we want.

“The moment you have a situation where you are really in control of things, that is to say the future is completely predictable, you will see that a completely predictable future is not what you want… What you want is a surprise.”

We needn’t figure out a surprise, just as we needn’t strive to figure out what we want.

Instead, by turning our attention to something all-encompassing, what we need underneath the want, and perhaps most importantly, enjoying where you are at and what you can create right now, not what you want to in the future.

When we do focus on just that, we might just recognise the moments and people that take our breath away.